Richard's downfall

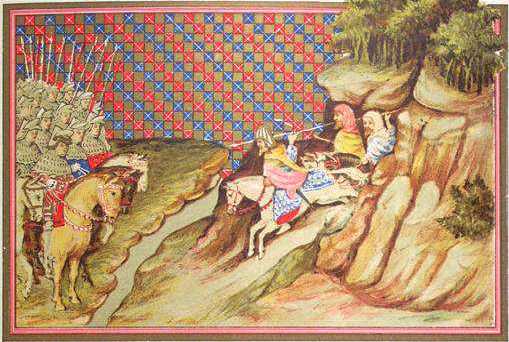

Modern historians agree with Shakespeare that Richard's downfall resulted from two fatal errors: the ill-considered seizure of Lancastrian estates upon John of Gaunt's death (an unforgiveable violation of the fervently guarded laws of inheritance*); and a badly timed expedition to secure control in Ireland.

The first error made an enemy of Henry Bolingbroke, the deprived Lancastrian heir, as well as encouraging the nobility to sympathize with him; and the second error enabled Bolingbroke to return from exile and establish strong enough support to outmatch the king when he rushed back from Ireland. Richard was forced to abdicate, and Henry's usurpation of the throne (legitimized by Parliament*) founded the Lancastrian dynasty.

Richard was dishonoured*, and became a forlorn prisoner* at Pontefract Castle, where he was probably murdered by forced starvation* in 1400.

Richard and the Essex Rebellion

During Queen Elizabeth's reign the Earl of Essex led a rebellion against the crown. Although this rebellion failed, Essex and his co-conspirators did succeed in rallying a significant amount of support both in England and abroad. One of the ways Essex convinced people of the validity of his rebellion was to liken Elizabeth to Richard. Essex not only patronized and applauded productions of Shakespeare's Richard II, but he went so far as to pay for a production to be staged for him and his followers the night before the rebellion. Essex's goal in this was to compare himself to Henry of Lancaster and Elizabeth to Richard in order to justify his rebellion.

Footnotes

-

Bolingbroke's inheritance

Henry Bolingbroke, later Henry IV, was also Duke of Hereford. In Shakespeare's Richard II his uncle argues with Richard:

Take Hereford's rights away, and take from Time

His charters and his customary rights,

Let not tomorrow then ensue [follow] today;

Be not thyself. For how art thou a king

But by fair sequence and succession?

(2.1.195-99.) -

Deposing a king

Adam of Usk wrote:

Next, the matter of setting aside King Richard, and of choosing Henry, duke of Lancaster, in his stead, and how it was to be done and for what reasons, was judicially committed to be debated on by certain doctors, bishops, and others, of whom I, who am now noting down these things, was one. And it was found by us that perjuries, sacrileges, unnatural crimes, oppression of his subjects, reduction of his people to slavery, cowardice and weakness of rule . . . were cause enough for setting him aside. . . ."

(From The Portable Medieval Reader.) -

A reflective Richard

Adam of Usk, who claimed to have visited Richard in the Tower where he died, reported some of the king's last, disillusioned thoughts:

And there and then the king discoursed sorrowfully in these words: "My God! a wonderful land is this, and fickle; which hath exiled, slain, destroyed, or ruined so many kings, rulers, and great men, and is ever filled and toileth with strife and variance and envy."

(From The Portable Medieval Reader.)Shakespeare's Richard meditates on time and fortune (see 5.5.1-66).

-

Richard's death

Adam of Usk writes of Richard's final days:

And now those in whom Richard, late king, did put his trust for help were fallen. And when he heard thereof, he grieved more sorely and mourned even to death, which came to him most miserably on the last day of February [1400], as he lay in chains in the castle of Pontefract, tortured by Sir N. Swinford with scant fare. . . .

(From The Portable Medieval Reader.) -

Naked dishonour

And Richard, late king, as gloriously as he in the morning departed from that town, so irreverently was he that afternoon brought into that town. For his body was despoiled to the skin, and nothing was left about him so much as would cover his privy member. . . And thus ended this man with dishonor as he that sought it; for he had continued still protector and have suffered the children to have prospered according to his allegiance and fealty, he would have honorably been lauded over all, whereas now his fame is darkened and dishonored as far as he is known.

(The Great Chronicle of London)